The daily struggle against COVID-19 has overshadowed a battle healthcare workers have been waging for decades: the fight against sepsis.

More than 1.7 million Americans are diagnosed with sepsis each year and it kills over 270,000 of them — more than breast cancer, prostate cancer, and AIDS combined.

“The incidence of sepsis is continuing to increase each year,” says Aaron M. Nolan, EMHA, BSN, RN, Director of Emergency Services at Methodist Richardson Medical Center.

What is sepsis?

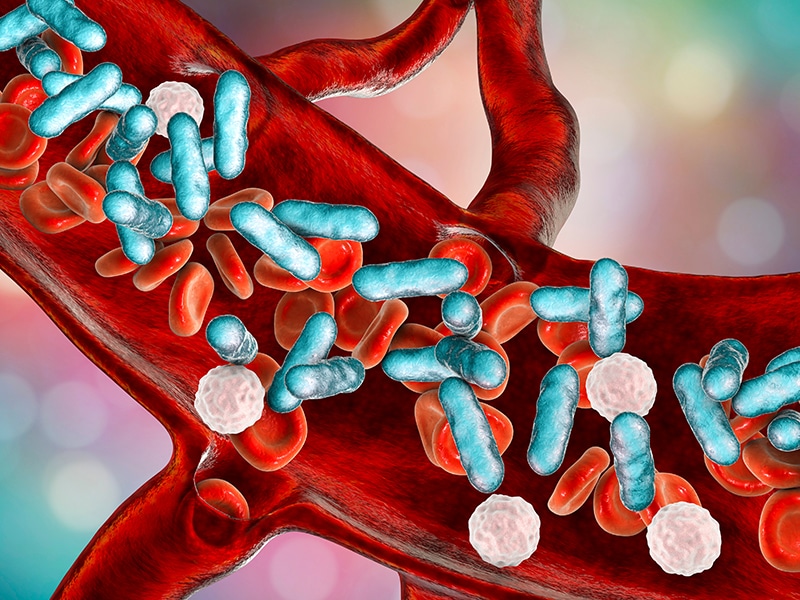

Sepsis is the body’s extreme response to an infection. Without treatment, it can set off a chain reaction called septic shock that leads to tissue damage, organ failure, and death.

“All types of infections can lead to sepsis,” Nolan says. “It is important that if someone develops signs of sepsis they seek help quickly.”

When it comes to the symptoms, Nolan says, “It’s all about TIME”:

- T = temperature above 100.4 or less than 96.8

- I = infection — cough, difficulty breathing, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain can all be signs of the underlying infection

- M = mental changes, confusion, drowsiness, or difficulty waking up

- E = extreme pain or illness

Other symptoms include a high heart rate and clammy or sweaty skin, Nolan says.

What causes it?

The underlying infection can be caused by a variety of factors, from bacteria like a urinary tract infection to a fungus like a yeast infection, or even a parasite like pinworms.

Sepsis can also be caused by viruses like the flu or COVID-19, although that’s not common, says Les Cler, MD, FACP, CPE, Chief Medical Officer for Methodist Dallas Medical Center.

“The majority of people with COVID-19 do not develop sepsis,” Cler says. “However, it is important for everyone to be alert.”

It’s estimated that 1 in 3 patients who die in a hospital suffers from sepsis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Who’s at risk?

The following groups are at the highest risk:

- Older adults

- Children under 1-year-old

- Pregnant women

- People with chronic conditions like diabetes, kidney or lung disease, and cancer

- Patients with a weakened immune system or who recently used antibiotics or steroids

- People with wounds or other injuries

How to stop it

There is something that sepsis does have in common with COVID-19: The ways to prevent sepsis should sound familiar.

“The best way to reduce your risk of sepsis is to wash your hands frequently and practice social distancing by staying home and limiting contact with other people,” Cler says.

If you suspect you might be suffering from sepsis, it’s “TIME” to talk to a doctor and seek help.

“If you have symptoms of sepsis,” Cler says, “come to the emergency department for further evaluation.”

Learn about the differences between COVID-19, the flu, and a common cold.