The prospect of open-heart surgery to replace a narrowing heart valve worried Kerry Walton, whose father had bypass surgery years ago and suffered terrible complications.

Fortunately for Kerry, a 68-year-old interior designer, retired Realtor, and avid traveler, Methodist Dallas Medical Center offered him a minimally invasive option known as transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

“My father was in the ICU for 27 days, and it was not a pleasant procedure,” Kerry says. “I spent one night in the hospital.”

While a quadruple bypass is a far different task than replacing a heart valve, it hasn’t been that long ago that both procedures required open-heart surgery.

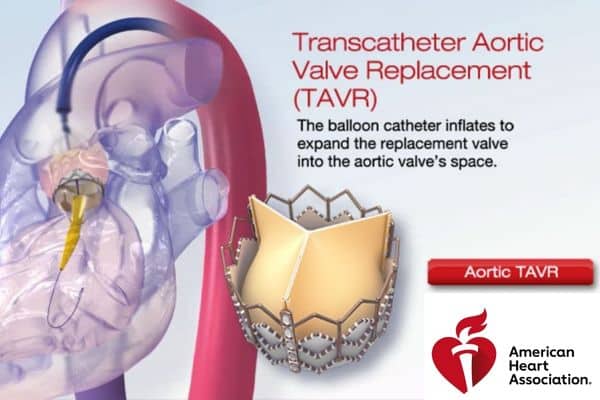

That changed with TAVR, a procedure that involves using a catheter to thread a manmade valve through the femoral artery to the heart, then opening it “like an umbrella” to replace the old valve, says Nasser Khan, MD, medical director of the structural heart program at Methodist Dallas.

“TAVR is a huge game-changer. It’s amazing technology.” — Nasser Khan, MD

After Dr. Khan performed Kerry’s procedure in August 2022, he was on his feet later that day, discharged within 24 hours, and within a month he was on his way to France for a previously scheduled trip.

“The whole team at Methodist Dallas has been phenomenal,” Kerry says. “Now I feel like I’m free to move about the cabin.”

DIAGNOSIS OF STENOSIS

Not that long ago, moving was a struggle for Kerry, who was diagnosed with aortic stenosis a couple of years ago by another cardiologist.

This condition involves the narrowing and stiffening of the heart valve as it calcifies with age. As a result, the heart must work harder to pump enough blood from the left ventricle through the narrowed valve and into the aorta, the fuel line for the body.

Symptoms of aortic stenosis include chest pain, fatigue, shortness of breath during exertion, and even fainting. Without treatment, it can lead to congestive heart failure and increase mortality.

WHO IS TAVR FOR

With his father’s heart disease in mind, Kerry sought a second opinion from Dr. Khan because his fatigue was making life miserable. He determined Kerry’s stenosis was so severe, “we needed to do something.”

But first Dr. Khan and his team had to determine whether Kerry was a good candidate for TAVR, rather than the more traditional open surgery that Kerry was dreading.

“His dad had open heart surgery,” Dr. Khan says, ”and in the past, that was the only way we could replace a valve. The patient had to stay in the hospital, there was a longer recovery time, and potentially, surgery-associated complications.”

TAVR, also called TAVI for transcatheter aortic valve implantation, was once reserved for patients in their 80s who were at high risk for surgical complications. Now some moderate- and even low-risk patients in their 60s and 70s are eligible for the minimally invasive alternative.

To Kerry’s relief, TAVR was the best option for him, and Dr. Khan quickly set the wheels in motion, scheduling the procedure within a matter of weeks of meeting Kerry.

NEW VALVE, NEW KERRY

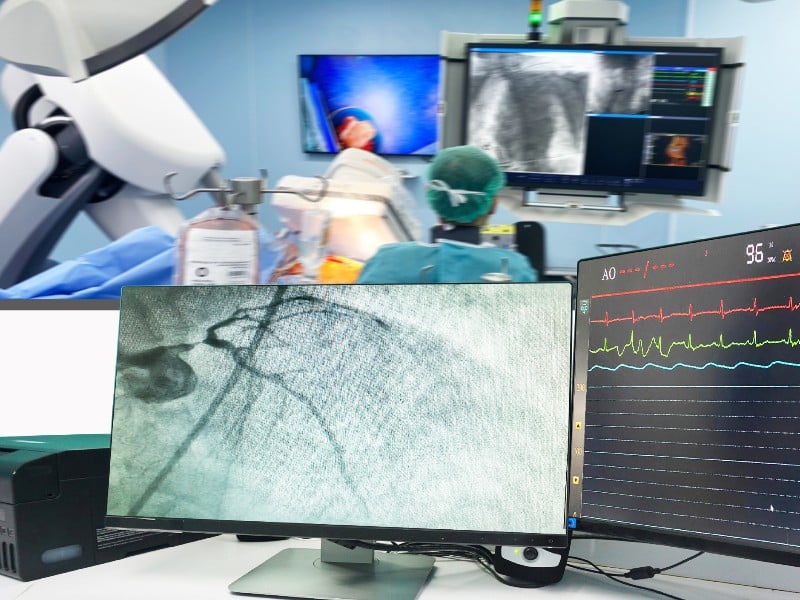

On the day of his procedure, Kerry was wheeled into the operating room to find a hive of activity, including his surgeon, the interventional cardiologist, anesthesiologist, cath lab technicians, and nurses.

“I was amazed at the number of people involved in the procedure,” he says. “The staff is so well trained, and they go out of their way to help.”

In fact, Kerry was so impressed by the people he met at Methodist Dallas that he decided to volunteer as a member of the Methodist Hospitals of Dallas Guild.

“A good friend of mine is president of The Guild,” he says. “She asked me to join, and I’m thrilled to be giving back to Methodist a bit.”

DON’T DOWNPLAY FATIGUE

Now working to improve his fitness level with a trainer at Methodist Dallas’ Folsom Fitness Center, Kerry has the energy again to help the Guild organize fundraisers and continue his travels – from France to Egypt to Bali, Indonesia, next.

Dr. Khan says Kerry’s case proves that retirement doesn’t necessarily mean slowing down, and he encourages anyone who’s finding themselves fatigued not to just chalk it up to aging.

“The natural inclination is to sort of downplay it: ‘Oh, I’m getting older, probably just my age,” he says. “But it may be a tight valve. And there may be a minimally invasive option to correct it.”