Imagine struggling for breath every time you go for a stroll, bike around the neighborhood, or fetch groceries. This is the reality facing many of the 3 million Americans living with emphysema, a type of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

There is no cure for emphysema, which gradually develops as a result of exposure to smoking, air pollution, and chemicals. The only ways to manage the worst symptoms are medication and surgery, and in worst-case scenarios, patients require lung transplants.

But a nonsurgical technique called endobronchial valve therapy, or EBV, may offer an alternative, says David Mason, MD, thoracic surgeon on the medical staff at Methodist Dallas Medical Center.

“This therapy is relatively new,” Dr. Mason explains. “For many people, their quality of life and their ability to carry on their daily activities are significantly improved.”

He discusses how this minimally invasive procedure can alleviate severe symptoms without a single incision.

HOW IT WORKS

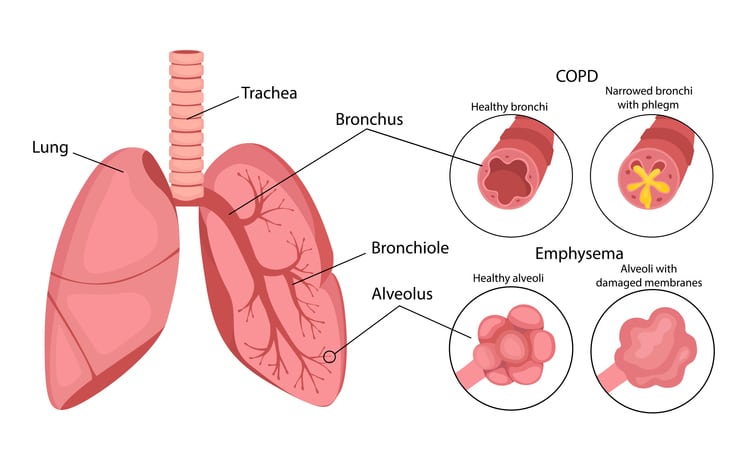

Emphysema damages lung tissue and the alveoli, preventing the tiny air sacs from taking in oxygen.

“Emphysema destroys the architecture of the lungs,” Dr. Mason says. “Essentially, air is trapped within the lungs, so they inflate and stay that way. You’re not really taking in oxygen or eliminating carbon dioxide.”

For patients with COPD, healthy parts of the lungs are crowded by the diseased portions of the lung, and overall efficiency is diminished.

“In most patients, the distribution of emphysema is uneven,” Dr. Mason adds, “meaning certain parts of the lungs are preserved and functional, and others play no role in respiratory function other than to take up space.”

While there is no repairing the damaged tissue, experts have found a way to release the trapped air and improve overall lung function.

Doctors can strategically place tiny one-way valves in the bronchi to prevent air from entering the diseased portion of the lung while allowing previously trapped air to escape. In effect, the damaged parts of the lung collapse while healthy parts are allowed room to function.

It provides patients a better option than lung volume reduction surgery, which requires physically removing damaged lung tissue, Dr. Mason says.

WHO SHOULD GET EBV?

There are certain criteria patients need to meet before they are considered for treatment.

First, they should generally have somewhere between 20% to 50% remaining lung function, which is determined through breathing tests, Dr. Mason says.

As with most other procedures, EBV does carry some risk of complications, including a collapsed lung and pneumonia. So if your lung function is at less than 20%, the risks will outweigh the potential benefits.

“The general side effects profile is relatively small,” Dr. Mason adds.

Second, how the disease is spread through your lungs also makes a difference. Using CT scans, physicians can identify which areas of the lungs are most affected.

“It’s better if the damage is concentrated in one area, preferably at the top of the lungs,” Dr. Mason explains. “If it is all throughout the lungs, there is a risk of the valves taking away functional alveoli as well as dysfunctional ones, which is suboptimal.”

A computer program is used to identify where the valves should be placed — essentially providing a roadmap. Usually, surgeons place about three or four valves per lobe of the lung, depending on severity, Dr. Mason says.

NONSURGICAL AND MINIMALLY INVASIVE

Surgeons use a bronchoscope to place the valves in the patient’s airways while they’re sedated with general anesthesia.

“There are no incisions, and after it’s done, we usually monitor the patient at the hospital for about three days,” Dr. Mason explains. “Sometimes they notice a change immediately, and sometimes it takes a few months before they appreciate the improvement. In general, it takes some time for their chest and lungs to reconform.”

Dr. Mason recommends his patients undergo pulmonary rehab — before, after, or both — which includes breathing and other exercises, for a better outcome.

This therapy is still a growing area of research, he says, but it can potentially improve the quality of life for many people who have few other options.

“These are not people with mild symptoms. They are people who can’t go about their daily lives without trouble breathing,” Dr. Mason clarifies. “It won’t allow them to run a marathon, but it can give them the ability to do things they couldn’t before — like playing with their kids or grandkids or going for a walk.”