For Chuck Roe, a heart attack struck “out of the blue” — and without the usual warning signs, requiring a stent and immediate surgery.

Not long before, the assistant director of fine arts at Mansfield ISD had gone through a battery of stress tests. They all came up clean, he says, and he had no previous history of heart problems.

So when he felt weak and started sweating one morning while taking his daughter to school, he assumed he had COVID-19. He figured he should go home and climb back into bed.

“It was a close call,” Chuck says. “If I’ve learned anything from this, it’s don’t look for ‘typical’ heart attack symptoms.”

That’s good advice, says Steven P. Havard, MD, cardiologist on the medical staff at Methodist Mansfield Medical Center who treated Chuck.

“All too often, patients expect the symptoms of a heart attack to be intense,” Dr. Havard says, “when in reality they often go unnoticed.”

A mural sponsored by Methodist Mansfield adorns Flying Squirrel Coffee Co. in downtown Mansfield.

SILENT HEART ATTACKS

In fact, silent myocardial infarctions (SMIs) account for a significant number of heart attacks. They’re often so brief and mild that the patient might confuse it for something else entirely.

They might confuse their fatigue for not getting enough sleep or mistake pain in their throat or chest as simple heartburn or indigestion. It’s only later that they realize what damage was done.

“A silent myocardial infarction can scar the heart,” Dr. Havard says, “potentially weakening a patient enough that a subsequent heart attack becomes that much more dangerous.”

Chuck felt no crushing pain, just a tightness in his chest and a “horrible sweat.” It was his wife, Kristy, who urged him to seek immediate care — and likely saved his life, Chuck says.

“If I would have gone home and gone to bed,” he says, “I wouldn’t have woke up.”

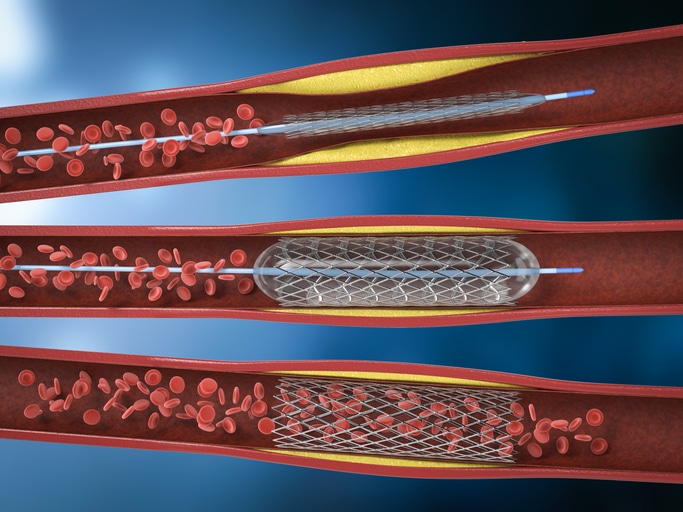

Opening a clogged artery after a heart attack with angioplasty involves inflating a balloon catheter and leaving behind a stent.

ARTERY 100% BLOCKED

Chuck was quickly transferred from a standalone emergency room to the cardiac catheterization lab at Methodist Mansfield.

There he would learn that one of his arteries was 100% blocked, and he’d need a stent to open it.

These tiny mesh tubes are inserted into a blocked artery using a balloon catheter. The balloon is then inflated, and the stent scaffolding locks in place, opening the artery to give the heart the blood it needs.

Dr. Havard and the rest of the cath lab team used an incision in Chuck’s wrist to place the stent and get the blood pumping again.

Chuck Roe shows the spot on his wrist where the catheter was inserted.

INSERTED THROUGH WRIST

While balloon angioplasty is nothing new, the minimally invasive procedure has historically been performed through the femoral artery in the groin.

Using a radial artery, which supplies blood to your hand, isn’t a method offered at all U.S. hospitals, but it has been catching on — and for good reason.

The radial artery is easier to access and much smaller than the femoral artery, so the risk of bleeding is lower. Also, patients tend to recover more quickly from a transradial access (TRA) angioplasty, and they don’t have to lie still for several hours after the procedure, as in a femoral access procedure.

In Chuck’s case, he was in a recovery room just two hours after he dropped his daughter off at school. Two days after that he was out of the hospital and beyond grateful for the care he received.

“This was my first stay in a hospital,” Chuck says. “The nurses we had were amazing, and everyone was so caring and careful.”