There’s no mistaking a passing dizzy spell for a bout of vertigo, a frightening loss of balance often accompanied by the sensation that the world is spinning. What’s more, chronic vertigo could be a critical warning sign.

Most of us have experienced dizziness or lightheadedness, perhaps after overdoing it at the gym or standing up too quickly first thing in the morning. Usually the feeling passes after a few moments.

Vertigo sets itself apart because it signals another condition, from a minor ear infection to a major stroke, and its debilitating effects can include chronic fatigue, queasiness, and nausea bad enough to cause vomiting.

A doctor can help you determine the cause and how concerned you should be, says Frederic Nguyen, MD, neurologist on the medical staff at Methodist Richardson Medical Center.

“Vertigo and dizziness affect 15% to 20% of adults and are among the most common reasons for medical office visits,” Dr. Nguyen says.

Not every dizzy spell is a cause of concern, but there are a handful of warning signs where you should seek help.

“There are ‘red flag’ signs, which should alarm patients to seek more urgent of immediate evaluation,” he says.

SEEK HELP F.A.S.T.

Don’t delay seeking medical help if vertigo manifests itself suddenly and is accompanied by stroke-like symptoms, such as numbness in the face or arm or slurred speech.

“The onset is important,” Dr. Nguyen says. “Sudden onset of new vertigo can be concerning, particularly if associated with other symptoms like those accompanying a stroke.”

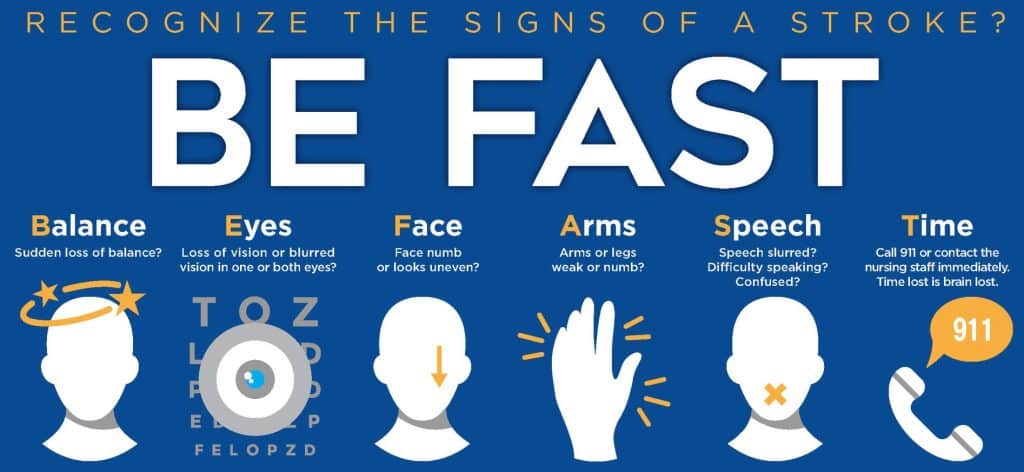

Keep in mind the most common warning signs of a stroke by remembering the acronym BE FAST:

TWO TYPES OF VERTIGO

There are two types of vertigo: central, named for the central nervous system, and peripheral, the more common type, associated with an inner-ear problem.

Central vertigo is caused by a “glitch” in the cerebellum, the small section of the brain where it meets the spine. This is where our brain’s balance control is based, and a stroke could throw that system off.

Peripheral vertigo can be caused by a range of inner-ear problems, the most common being BPPV, or benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Dr. Nguyen says.

In patients with BPPV, the tiny calcium crystals (known as canaliths) that help us keep our balance break loose and float in the liquid within the inner ear. These crystals can get dislodged whenever your head changes position, whether you’re rolling over in bed or standing up.

What triggers BPPV isn’t entirely clear, but it grows more common with age and can sometimes be attributed to an ear or head injury or constant exposure to especially loud noises.

Other ear conditions that can cause peripheral vertigo include labyrinthitis, typically caused by a viral infection, and Meniere’s disease, caused by too much fluid in the inner ear. People with frequent migraines may also suffer from vertigo, even when they’re not having a headache.

HOW TO TREAT IT

There is a range of treatment options to consider from prescription medication to simple rehabilitation exercises, but Dr. Nguyen stresses the importance of diagnosis.

“We must identify the potential causes, then we can tailor the treatment,” he says.

Peripheral vertigo can often be treated with vestibular rehab therapy (VRT), an exercise program designed to improve balance and resolve dizziness. For example, using the Epley maneuver — a series of head and body motions — can help a patient resolve vertigo by repositioning the crystals in the inner ear.

Dr. Nguyen says the best outcome depends on a multidisciplinary approach that combines such self-therapy with rehab and treatment by a specialist such as an ear, nose, and throat doctor.

“There are also some anti-dizzy medications available by prescription and over the counter,” he says. “Just know that chronic vertigo is something you don’t have to tolerate. See a doctor.”